Potato growers address ongoing water worries through research

Water is one of the earth’s most precious resources. Clean water is vital to maintaining the health of humans, plants and animals alike. It is also necessary for sanitation and food processing.

Unfortunately, water quality and quantity are often taken for granted, especially in developed nations. Climate change, however, has put a spotlight on water issues, prompting potato industry experts to look for solutions to challenges that impact both water quality and availability.

BREEDING FOR RESILIENCE

Potatoes are sensitive to moisture stress; both high and low moisture levels strain plant production. Potato crops need high soil moisture levels to thrive, yet they grow best in well-drained, sandy loam to silt-loam soils, which have very little water-holding capacity.

Breeding for greater resilience is one of the main objectives of the University of Maine’s (UMaine) potato breeding program.

Mario Andrade, assistant professor of potato breeding and genetics, said that while the program does not focus specifically on drought tolerance, trials are conducted without the use of irrigation. Doing so allows the researchers to select cultivars that are naturally more resistant to water stress.

Moisture stress is not new to Maine. In 2020, the state experienced a severe drought that resulted in a 20% reduction in potato yields. Less than 10% of potato acres in the state are under irrigation, which means some genetic tolerance is crucial to the crop’s success.

To test for tolerance to water stress, new varieties that come out of UMaine’s breeding program are sent to North Carolina and Florida, where they are selected for heat resistance.

This is done through a strategic partnership between seven institutions, including Penn State, Virginia Tech and Cornell. The partnership was developed 20 years ago.

“In the U.S., we always try to have a potato that can grow in a wide range of places,” Andrade said. The partnership, he added, allows them to do this.

To date, the program’s most successful cultivar is Caribou Russet, a variety that farmers have said shows good resistance to drought and heat, Andrade said.

MITIGATING WATER QUALITY ISSUES

At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, associate professor and state Extension specialist Yi Wang focuses on sustainable vegetable production. This includes water management in potatoes. While earlier research efforts focused on drought tolerance, following a very wet year in 2018, the program switched gears and targeted water quality instead.

According to Wang, most of Wisconsin’s potatoes are produced in the Central Sands Region, which has sandy soil. Organic matter is less than 1%, which means water-holding capacity is extremely low. When precipitation surpasses 1 inch, either from rainfall or irrigation, everything leaches down to the groundwater table. The region’s groundwater table is very low, said Wang.

In some places, it’s as shallow as 10 feet to 20 feet from the soil surface. On top of that, potatoes are a very needy crop when it comes to fertilizer.

To avoid nitrate leaching, Wisconsin Extension specialists like Wang recommend growers split apply 250 pounds of nitrogen per acre, per growing season — 60% at planting, and 40% at the early-to-late tuber bulking stage.

“The split nitrogen application is more for avoiding the nitrate leaching issue, but even with that we are still facing potential nitrate leaching,” Wang said.

One of the solutions has been to use ESN, a slow-release nitrogen fertilizer. Producers have still reported issues with leaching, though, she added.

Wisconsin researchers are also using remote sensor technology and machine learning, including hyperspectral and multispectral imaging and ground-based robots, to monitor plant growth and improve weather forecasting. Having access to more accurate data allows farmers to make better use of decision-making tools like the 4R Nutrient Stewardship plan. Applying the right fertilizer source at the right rate in the right place at the right time could, ultimately, help farmers reduce nitrate leaching potential.

“Potatoes need nitrogen, and our system doesn’t hold nitrogen, so how do you find a balance?” said Wang. “That’s the question we’re trying to address right now with different strategies.”

BENEFITS FOR PRODUCERS

All water is not created equal; there are distinct differences between rainwater and irrigated surface or city water. Normal irrigation water can be hard due to high sedimentation and mineralization, and nutrients can lock up when sodium is present. Rainwater, on the other hand, passes through layers of atmospheric magnetic fields, picking up a charge as it does.

Magnation Water Technologies manufactures advanced water conditioning and correcting products that offer chemical-free, energy-free and maintenance-free solutions for sustainable water use. Its in-line conditioning product, Turbolator, utilizes physics, rather than chemistry, to condition water.

According to Mike Jenzeh, CEO, naturally charged rainwater better penetrates the ground, hydrates plants and improves nutrient uptake. This understanding was the impetus behind the development of the Turbulator.

Jenzeh said the approach reduces pumping costs, improves hydration, maintains nutrients, neutralizes pH, reduces saline content and separates gasses.

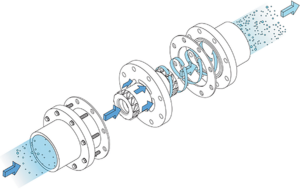

At the molecular level, non-water components, including dissolved gasses and particulates, are separated out. At the same time, magnets are used to induce charging, which causes perturbation that breaks up longer and flake-like structures. It also causes agglomeration or clustering, which lets common elements such as calcium pass through plumbing without sticking. The resulting ‘true’ water content has a reduced coefficient of friction when it meets piping, so pumps can move volumes using much less energy —as much as 10% to 15%.

“If you’re drinking the water, it hydrates more efficiently,” said Jenzeh. “If you’re using it for irrigation, it turns your irrigation water into rain-like water.”

“This product helps improve water penetration and betters water retention,” he added. “So (farmers) end up using less water. For average center pivots, it’s a savings of about 5 million gallons of water when they use this.”

Idaho potato grower Bryan Searle was introduced to Magnation water treatment products through one of his equipment salesmen. He decided to give it a try on a three-quarter mile long field. He was using one irrigation pivot on the south end of the field, and one on the north end. He installed the Turbolator on the north half of the field and left the southern half untreated.

“Our nitrogen levels, in fact, all of our levels were higher on those fields that were treated with Magnation,” Searle said. “We tested and monitored the crops throughout the year and we also found that the Magnation side was wetter than the south side.”

The increased hydration allowed Searle to intermittently shut irrigation off in the northern part of the field, helping him to save water.

“We saved about one week’s worth of irrigation,” he said. “At least 10% less water was needed on the Magnation side.”

Searle said he was also able to reduce fertilizer use on the field treated with the Turbolator.

“We used 30 units less of nitrogen, and still had higher petiole readings,” he said. At the time of installation, 30 units of nitrogen cost about $18 an acre. He was happy with the savings realized on the 130-acre piece of land.

Searle now has several units on parts of his 2,500-acre farm. Although he’s not been able to pinpoint why, he gets better results from aquifer water rather than surface water. He suspects it has something to do with pH but hasn’t had time to run proper trials.