The quest for an aquifer alternative

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was created in 1902 to aid agricultural development of arid Western states. A perfect candidate was Central Washington’s Columbia Plateau — a desert with fertile soil and the Columbia River passing through.

President Franklin Roosevelt authorized a dam, and the Columbia Basin Project intended to irrigate 1.1 million acres to attract settlers to farm this land.

The region is of critical present-day importance to the U.S. potato industry. Central/eastern Washington grows 23% of the nation’s potatoes, and in 2023, the state produced 99.7 million cwt of potatoes — second only to Idaho.

However, after decades of delays, the original irrigation vision is relying on a new project to achieve its goals and preserve the region’s water supply.

COMPLICATED HISTORY

Construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, begun in 1933, was completed in 1942, though irrigation was postponed during World War II in favor of electrical power generation for the war effort. Irrigation water arrived between 1948 and 1952, but costs escalated. The original plan, in which people receiving irrigation water would pay back the costs of the project over time, was repeatedly revised.

Farm plots, at first restricted in size, became larger, while government conflicts thwarted settlement goals. As the estimated cost for completing the project more than doubled between 1940 and 1964, it became clear that the government’s financial investment would not be recovered. Farmers who had taken up land on the unfinished portion, trusting they would eventually have the water they’d been promised, struggled to make a living. As a temporary measure, they were given permission to drill wells into the underlying aquifer until the project was completed.

Completion delays resulted in a drain on the aquifer. The Columbia Basin’s Odessa aquifer is the region’s domestic water supply, providing water to 25 area towns and cities, and evidence of depletion has been noted since the mid-1960s. There is increasing concern about the effect of deep-well irrigation.

SEARCH FOR SOLUTIONS

Michelle Kiesz is a fourth-generation farmer on the Columbia Basin project. Her great-grandfather arrived in the area in 1900 from Odessa, Russia, as did many of the families who farm in this basin. She joined the Columbia Basin Development League 10 years ago and is on the executive board.

“We advocate for completion of the project,” Kiesz said. “This is more than just about getting the wells off-line. It’s about how to get water to everyone out here. This is a federal project and these people were promised water in the 1930s and 40s.”

The Odessa Groundwater Replacement Program (OGWRP) is an aquifer rescue mission, with a plan to exchange, acre for acre, deep well irrigation with Columbia Basin Project surface water for 87,700 acres.

Clark Kagele, another fourth- generation farmer on a family farm in Odessa, is playing a key role in the program.

“We’ve been at this a long time. My father drilled his first well in the early 1960s,” Kagele said. “There is a water right stating that when the Bureau of Reclamation water shows up, the water right for the wells goes back to the state. All the wells were drilled with the expectation that there would eventually be water from the river.

“I was about 8 years old when we started the wells. My first job in irrigation was pipe trailer boy. In those days you had to buy enough main lines and hand lines to irrigate 80 acres, and you picked it all up and moved it to the next 80 acres — moving pipe all the time.”

Kagele’s father put in five wells, and all but one eventually failed.

“A couple were re-drilled down to 2200 feet. and the expense was mind- boggling,” Kagele said. “One is simply shut off. Water quality from deep wells is not very good for the land or the crops. I was very frustrated in all the years of failures.”

When a moratorium on taking water from the Columbia River was eventually lifted, a county commissioner in Lincoln County contacted Kagele.

“He said the moratorium had been lifted and we needed to go after the water,” Kagele said. “He hooked me up with Alice Parker with the Columbia Basin Development League, which has been in existence since 1962.”

GRASSROOTS PUSH

The league is a grassroots organization pushing for completion of the project while monitoring other water issues. Kagele and Parker, a league trustee, recruited an infusion of leadership and began to grow the organization, as well as interest in completing the OGWRP.

“We got great support from industry, especially the (Washington State) Potato Commission and Valmont Industries at Moses Lake,” Kagele said. “This gave us seed money to become an advocacy group. Over the years, many farm and processing industries have jumped on board to help support the effort to replace wells with river water.”

After about eight years, the state funded a detailed study that took a closer look at OGWRP options for shutting down deep wells and preserving the aquifer for domestic use.

“It turned into an aquifer rescue program rather than build the second half of the project,” Kagele said. “It was designed to see how many acres you could possibly irrigate economically from the canals and get as many wells shut off as possible.

“That was the option selected — to do pumping stations and pipelines.”

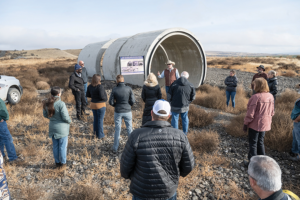

Eventually, the state came up with money to start designing a system 22.1 miles down the canal from Billy Clapp Lake at an area south of the freeway with few acres, Kagele said. The system, built by the Columbia Basin Irrigation District, has been running for a couple of years, he said.

FERTILE FUTURE

Federal dollars have also helped fuel the effort. For two years, the Natural Resources Conservation Service and other agencies have worked together to develop successful Regional Conservation Partnership Program grant proposals.

“The big success story is NRCS showing up with its program and deeming this a worthy conservation issue to preserve this aquifer,” Kagele said. “This will build three more systems. … As these are being constructed, the plan is to average whatever cost is left over after grant support on all the systems. If one system gets a total grant to build the whole thing, that lowers the price for everybody.”

Harold Crose with the Columbia Basin Conservation District has been working closely with farmers and is currently helping with planning and design to deliver water.

“The economic future of the area is at stake. About 30,000 jobs rely on this farming industry,” he said. “Processing plants, ag suppliers, etc. are a big part of the economy, creating billions of dollars. This fertile land grows many different crops and is one of the biggest producers of potatoes in the world.”

Farmers are appreciative of ongoing efforts to make the project work.

“It’s taken 10 years of intense work and many trips to Olympia and Washington, D.C. to promote the program and gather support,” Kagele said. “There is still a great deal of work to do.

“Food security is the ultimate goal, and finishing the entire Columbia Basin Project would be the gold medal.”