PVY: Study shows how different strains affect different potato varieties

Potato virus Y (PVY) is one of the most troublesome diseases potato growers face. The virus can have a backbreaking effect on a farm’s bottom line, both in terms of yield and in marketability of those tubers that are produced. In a recent online survey, Spudman readers said PVY concerns them the most of any potato plant disease.

PVY can cause unsightly potato tuber necrotic ringspot disease (PTNRD) and affect the size, gravity and number of tubers a plant produces. It can break the skin on tubers, which becomes an entry point for other pathogens and pests.

About a half-dozen strains of PVY currently are present in North America. They include:

- PVYN

- PVYNE-11

- PVYNTN

- PVYN:O

- PVYN-Wi (aka N-Wilga)

- PVYO

Researchers from the University of Idaho have been conducting PVY experiments at commercial fields and seed lots in Hermiston, Oregon, and Othello, Washington, since 2011. (Postharvest and storage studies also took place in Kimberly, Idaho.)

The basis of the trials is to see how different cultivars react to the various strains of the virus. Two of the leaders in the research, Nora Olsen and Alexander V. Karasev, both professors at the University of Idaho, presented an update on their findings during the Idaho Potato Conference and Ag Expo earlier this year.

Karasev said the Columbia Basin is ideal for PVY research because growers import seeds from around North America. Studies included keeping tabs on the progress of plants where the virus was present in the seed and plants that became infected later. They monitored plants while growing, as well as if and when tubers developed symptoms while in storage.

PVY is changing

N-Wilga (N-Wi) has become the most common strain, according to the research, which showed that Wilga accounted for approximately 70 percent of cases.

“PVY is changing,” Karasev said. “PVYO has been replaced by N-Wi. NTN is down as well (although still second). If you’re looking at (finding) resistance, then look at PVYN-WI.”

The cultivars used in the studies included Alturas, Bannock Russet, Clearwater Russet, Ranger Russet, Russet Burbank, Umatilla Russet, Waneta and Yukon Gold. The non-russets proved to be especially susceptible to the virus.

“One of the most susceptible is Yukon Gold,” Karasev said. “Also Waneta and Alturas.”

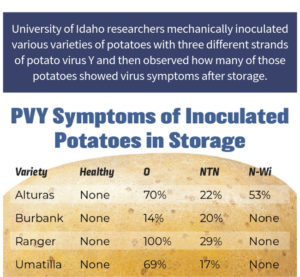

Alturas, especially, infected with N-Wi tend to show symptoms once in storage. Fifty-three percent of the Alturas inoculated with N-Wi showed symptoms while in storage, whereas the russet varieties held up much better in storage.

“One of our recommendations is to be very cautious if your Alturas have Wilga,” said Olsen, who added that Alturas from an Wilga-infected field should probably be shipped as soon as possible.

Among the russets, Burbank showed more susceptibility than other varieties. During a screenhouse inoculation study that focused on NTN, N-Wi and O, the infection rate was above 70 percent for Burbank for all three strains — and nearly 95 percent for N-Wi — yet infection rates were under 20 percent for for both Bannock and Clearwater, and even under 10 percent in multiple cases.

Burbanks actually held up better than the other varieties of not developing symptoms while in storage. Only 20 percent of Burbanks inoculated with NTN showed symptoms and 14 percent inoculated with O did. Olsen said it was surprising to see how many potatoes infected with O showed symptoms in storage. Ranger (100 percent), Alturas (70) and Umatilla (69) were at a much higher rate than Burbank.

“We never really thought of O being a strain that would provide symptoms, but they can in certain circumstances,” Olsen said.

Because of the variances between the different strains and uneven effects on different varieties, knowing which strain is present can be key for growers.

“It is really important to get those samples in so you know what strain you’re dealing with so you can respond appropriately to that strain and that variety,” Olsen said.

Studies also found that a higher percentage of plants show symptoms when the virus wasn’t present at planting than when it was. “That’s because seed-borne (infected) plants tend to die off early,” Olsen said.

Next steps

No grower wants PVY in his or her fields, but it commonly happens. When it’s present, the key, from a production standpoint, is avoiding the show of symptoms. The fallout from those symptoms can go well beyond just the virus itself.

“Symptoms, when they are there, can impact fry color, but also they break the skin of the potato often,” Olsen said. “That becomes an entry point for other diseases, whether it be soft rot or anything else. … So that’s one of the concerns we have on the symptoms, not just the fry color or aesthetic, but that they can be an entry point.”

Not surprisingly, research showed stressed plants produce symptoms at a much greater rate than non-stressed. The biggest thing a grower can do is maintain optimal plant health, Olsen said.

“It’s hard when you have, say 50 percent PVY out in that commercial field, having to decide do you put more nitrogen on it,” Olsen said. “We try to recommend to just try to minimize stress as much as possible in those fields and carry on as best as you possibly can.”

A portion of the Specialty Crop Research Initiative, which is scheduled to get underway this year, will focus on management and control of tuber necrotic and vector-borne viruses of potato. That also will include breeding research for resistance to PVY, as well as potato mop-top virus (PMTV) and tobacco rattle virus (TRV).