Mar 28, 2018Threat Assessment: Researchers make progress fighting old and new diseases

Our April issue focuses on research and we take deep dives into the latest efforts to fight major threats like dickeya and late blight. We also take a look at zebra chip and try to figure out if the pathogen is still as a big of threat as it was a decade or so ago.

Zebra chip

Zebra chip

When zebra chip burst onto the scene in the U.S. in the 2000s, it came as a nasty surprise for many growers and cost producers millions of dollars. A little over a decade later, is zebra chip still as serious of a threat as it was then, and do researchers have a better handle on how the disease works and how to fight it?

The answer to the first of those questions, is an emphatic yes according to Charlie Rush, who directs the research program in plant pathology at Texas A&M AgriLife Research in Amarillo.

“There is no question it is still potentially devastating,” he said. “They (growers) get where they have a low-pressure year and they stop worrying about it or they use their chemicals wisely and have good control for a few years and they start thinking, ‘it’s not really out there anymore, it’s not a problem, I can back off,’ and that’s when they get hurt.”

To answer the second question, researchers have made advances in knowing more about how the disease is spread by its vector, the potato psyllid, and how the disease manifests.

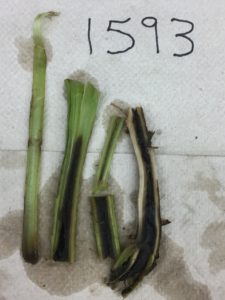

Dickeya

A new blackleg pathogen, Dickeya dianthicola, emerged in the eastern U.S. in 2015. Since then researchers have been working to find ways to control the disease, as it causes significant yield loss in potato crops. While progress in terms of control methods has been slow, growers who have adapted suggest best management practices have contributed to the disease’s decline.

While the disease’s decline could be attributed to weather conditions, which were mostly unfavorable to the development of the disease, Gary Secor, professor of plant pathology at North Dakota State University, attributes the drop-off to seed lot testing and growers’ due diligence.

“It is a bacterial disease, so we don’t have any really good chemicals that we can use to manage dickeya,” Secor said.

Late blight

Late blight

Late blight, caused by Phytophthora infestans, is typically not expected to be a problem in the Columbia Basin of Washington and Oregon because the disease is disfavored by the semiarid environment. Cool, wet weather with rainfall, ambient relative humidity above 90 percent, and temperatures of 7 to 24°C (44.6-75.2°F) favor late blight development. However, sprinkler irrigation modifies the environment within the potato crop canopy and increases the potential for late blight in semiarid regions. High humidity in the crop canopy favors sporulation of P. infestans and leaf wetness is crucial for infection.

The Columbia Basin is similar to other regions of the world where potato late blight is dependent on the physical environment for development. Foliage and tubers of potato cultivars grown in the region are susceptible to infection and aggressive genotypes of P. infestans are often present. When inoculum of P. infestans is present, only a favorable environment and sufficient time are needed for epidemic development.

How to get the full story

For management practices to help fight the spread of dickeya, the full details on how to manage your canopy environment to reduce risk of late blight, a cutting edge effort in Idaho to warn growers of fungal pathogens and a rundown of the full state of information on zebra chip subscribe and check out the full April issue of Spudman.