Soil health and potatoes

Soil health is taking a significant leap to the forefront of farming, and a large research project is underway for potatoes. The USDA-NIFA-funded project entitled Enhancing Soil Health in Potato Cropping Systems is overseeing a five-year study spanning 10 different states, eight of which have traditional potato cropping systems, to see if there is a measurable change in soil health while introducing sustainable practices.

There are a few major objectives of this study. The first is to set up specific small plots — both two-year and three-year rotations, each with certain adjustments — to see if there is any change in yield or productivity.

“We’re looking at some of the management practices that might enhance soil health. This could include adding cover crops to the system, different soil amendments, carbon amendments like manure,” said Carl Rosen, department head of soil, water and climate at the University of Minnesota. “We’re also looking at different rotations, and perhaps things like biofumigants.”

An indicator of change

The research teams are including fumigation in the list as a soil health management tool because as conventional treatments are compared with biological treatments, they’ll be measuring the effects on the microbiome and other soil health indicators.

While all eight states focus on region-specific cropping systems, they all contain at least one rotation with Russet Burbank for control purposes, but Russet Norkotah and Bannock Russet are also being examined.

Bannock Russet is being included because of its resistance to verticillium.

“We’re extracting DNA from soils, and we’re basically using this process called DNA and meta barcoding. We’re able to look at the taxonomic composition of the entire microbial community that’s present in the soil,” said Ken Frost, associate professor and Extension plant pathologist at Oregon State University (OSU).

There is a particular interest in using the soil microbiome as an indicator of change when using various practices.

For example, Rosen and his team found a grower field where part of the field had been in potatoes for 40 or 50 years on a two-year rotation. The other part of the field had not grown potatoes at all and was unmanaged.

In the field with potatoes, there was bacteria that could break down urea. But in the unmanaged field, those bacteria were barely existent. Only after a couple of months of growing potatoes in the new field did Rosen begin seeing an increase in those bacteria.

“There’s not a lot of overlap in the microbial communities across the nation, which I found to be somewhat surprising working in the same cropping system,” Frost said. “I would have thought there would be a fair amount of overlap in the microbial communities.”

Another objective is to figure out if the practices will be economically viable, impacting either a better yield or cutting costs for a grower’s management of the field. Economists are presently looking at the data.

Time and biofumigants

Outreach is another significant objective. There are a number of resources on the website (https://potatosoilhealth.cfans.umn.edu/), as well as presentations and videos. Given the scope of the project, the data is still being computed, but there have been some interesting developments.

“We did find, at least in Minnesota — I can’t say what happened in all the other states yet — but we can say that the biofumigation treatments tested are somewhat effective,” Rosen said. “They’re not maybe quite as effective as fumigation, but we do see some yield benefits to the biofumigation treatments relative to no fumigation at all.”

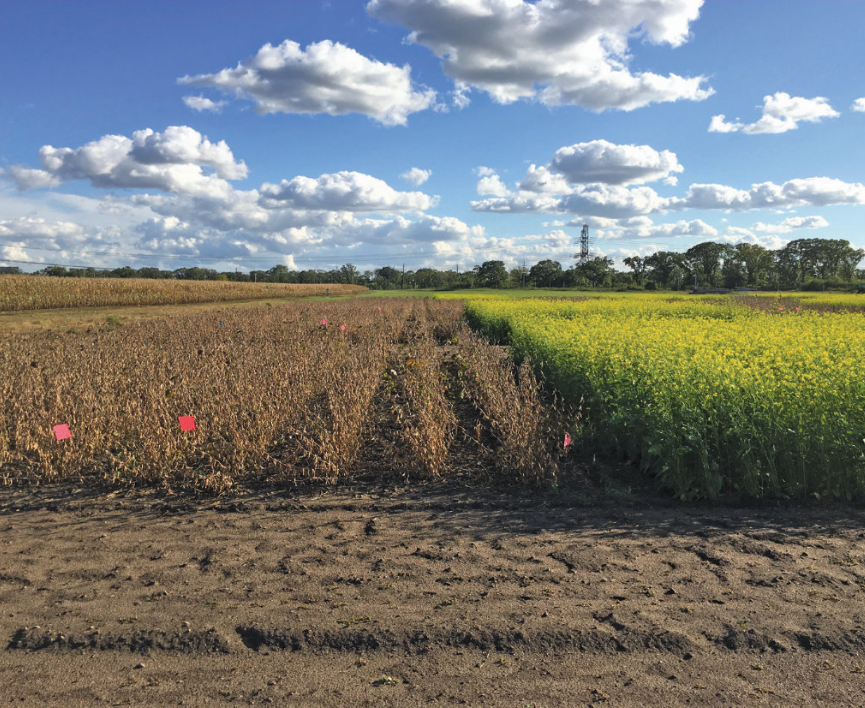

The biofumigant used in the Minnesota rotation is primarily mustard, paired with a previous crop of dried peas and a rye cover crop following mustard incorporation. Mustard, when crushed, produces chemical compounds called glucosinolates, which have a pungent odor. Mustard should be chopped or crushed and incorporated into the soil, so that the chemical is activated and released.

The studies revealed a bump in benefits to biofumigation over not fumigating at all. It seemed to be more effective in a three-year rotation than in the two-year rotation.

“The longer rotation you have, the more benefit you will see,” said Rosen. This includes reduced soilborne disease, Frost added.

There’s also the idea of shortening rotation, concerns about soil degradation, and increased disease pressure if rotations are shortened. There was a lot more verticillium found in the two-year rotation, even with fumigation, than in the three-year rotation.

A broad lens

There is a looming challenge in regard to potatoes and soil health: The bottom line with soil health is minimal soil disturbance.

This study, given its scope, shouldn’t be viewed through one particular lens. What the team is looking at is not only the chemical properties, but also the biological and physical properties of the soil.

“You can’t really just look at one thing in isolation,” Rosen said. “They’re all related; one thing will affect the other.”

With so many disparate elements, there’s a lot to consider when moving forward — from protecting against verticillium and nematodes using traditional fumigation or biofumigation, to changes in the microbiome due to cropping practices, to the economics of soil health practices.

“It’s a complex thing. There are no simple solutions,” said Rosen, “but we’re taking it one step at a time.”