Progress on Dickeya

A new blackleg pathogen, Dickeya dianthicola, emerged in the eastern U.S. in 2015. Since then researchers have been working to find ways to control the disease, as it causes significant yield loss in potato crops. While progress in terms of control methods has been slow, growers who have adapted suggested best management practices have contributed to the disease’s decline.

While the disease’s decline could be attributed to weather conditions, which were mostly unfavorable to the development of the disease, Gary Secor, professor of plant pathology at North Dakota State University, attributes the drop-off to seed lot testing and growers’ due diligence.

“It is a bacterial disease, so we don’t have any really good chemicals that we can use to manage dickeya,” Secor said. “One of the ways that we believe it spreads is during handling. When you’re cutting, loading or harvesting there’s a chance for bacteria to spread and contaminate other potatoes.”

The bacteria, he said, need a wound to enter, so applying disinfectants can reduce populations, but oftentimes the bacteria is already inside the tuber’s vascular system where disinfectants can’t reach.

“They can only reduce populations on the equipment that’s used to handle them,” he said.

Antibiotics were proposed as a possible solution to dickeya, but Amy Charkowski, professor and head of bioagricultural science and pest management at Colorado State University, said they’re really not an option since they’re very costly.

“Growers have the option of copper sprays or products such as Double Nickel for blackleg management and these products may reduce losses, but in severe cases, they are unlikely to provide substantial improvements,” she said.

Secor agreed.

“We’re really limited as far as managing dickeya through the use of any kind of chemical control or bactericides, except for general disinfecting,” he said.

Dickeya bacteria do not survive for a long period of time either on the soil or on equipment. Simply avoiding wet conditions helps to manage the pathogen as well.

So far, there are no dickeya-resistant potato varieties, but there are some varieties that seem susceptible. No research has been done in this area yet, Secor said, as the disease is too new. The best management practice so far is to plant clean seed, he said.

“The best management practice we have is to find or identify a seed lot that does not have dickeya and to plant that,” he said.

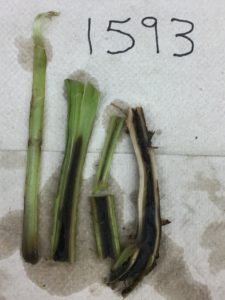

This can be difficult, though, since dickeya doesn’t express symptoms in potatoes in storage. Expression in the field is limited as well. A laboratory test is necessary in order to determine if a seed lot is infected or not. Secor said they’ve developed a testing procedure to test seed lots for the presence of dickeya.

At Colorado State University, Secor and his colleagues have been looking at how dickeya spreads during the cutting and handling of seed. They’re also looking at how it spreads in the field. They plan on repeating trials and making results available as soon as they’re ready. What they did find, though, was that dickeya does spread in the field if tubers are inoculated, and it will move in the soil, especially in irrigated crops.

Jay Hao from the University of Maine has been testing chemicals to identify new possibilities for management. Results are a long way off, though.

In 2016, Charkowski applied for a Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant to conduct multi-state research on dickeya. The grant was approved and funded last October and the researchers are now in the beginning stages of the project. In the meantime, the group has made progress with other sources of funding.

“We now know that multiple dickeya species can be found in North American potato and that the distribution of the species varies across states,” Charkowski said. “We have improved detection methods and more data on cultivar responses to blackleg and soft rot.”

“We’ve also increased the number of plant disease diagnostic clinics that offer testing and have worked on standardizing testing methods in the U.S. for these pathogens,” she said.

Research on the epidemiology of the disease has revealed that the disease is even more complex than once thought. A comparison of data from Carol Ishimaru of the University of Minnesota shows that multiple dickeya and pectobacterium species are commonly found in potato.

“Comparison of her data with data from other states shows that the most common species found in the Midwest, western states, and the upper East Coast differ,” Charkowski said.

For example, P. parmentieri and D. dianthicola are the species commonly found in Maine, whereas P. atrosepticum and D. dianthicola are found in Colorado. Similarly, D. chrysanthemi and D. dadantii are found in the upper Midwest, but do not seem prevalent in other areas.

“Because so many different species cause essentially the same symptoms in potato and because we are finding important biological differences among these species, it will make breeding for resistance and developing management tools more difficult than for other common potato diseases,” Charkowski.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MANAGING DICKEYA

Until there’s a more viable solution, the best recommendation researchers can offer is avoidance. First, be sure to test seed potatoes for dickeya.

“If you are in a high-risk situation for these diseases, such as producing early generation seed in a greenhouse or in the field, or in an area where losses to blackleg can be severe, such as East Coast states from Pennsylvania through Florida, then you should make every effort to plant seed lots that have low levels of pathogen, or better yet, that are free of dickeya,” Charkowski said.

To avoid spread, seed potato growers should sanitize equipment both at planting and at harvest between seed lots. Many pathogens, including dickeya, will spread during planting and harvest operations.

Finally, if at all possible, do not use surface water to irrigate seed potato crops.

“Dickeya and pectobacterium both can survive well in surface water and spreading through irrigation water is one way that they may be able to infect previously-healthy potatoes,” Charkowski said.