Pest detectives: MSU researchers hot on trail of potato early die culprits

Growing up on her family’s farm in Rancagua, Chile, Marisol Quintanilla became an astute observer of nature. She took note of the plants, insects and other flora and fauna essential to life on the farm, which grew table grapes and other crops.

She noticed one thing in particular.

“We had a big pile, a big mountain of chicken manure, in one part of

the farm to spread, and wherever that mound of chicken manure was, nothing would survive. All the insects would die, the worms would die, the plants would die. There would be no weeds. It was sterile,” she said. “So I was very aware that manure, especially chicken manure, is a biocide. In general, it kills life.”

That early observation would become the basis of a research project Quintanilla, an assistant professor in the Department of Entomology at Michigan State, is conducting.

Chasing the culprits

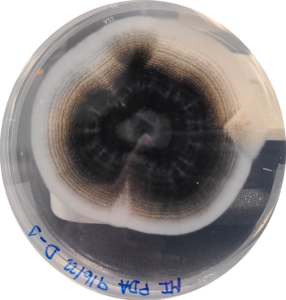

In May, MSU received a $750,000 grant from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture to develop sustainable methods of managing potato early die complex, a constant, insidious threat facing potato producers. The disease, caused by the convergence of a fungus, Verticillium dahliae, and a nematode, Pratylenchus penetrans, compromises a potato plant’s health before it reaches maturity and has the potential to reduce yields by as much as 50%.

Combating it is especially crucial in Michigan, the nation’s leading producer of chipping potatoes, where the potato industry contributes more than $1.24 billion to the state’s economy.

Quintanilla heard from Michigan growers and MSU research collaborators about the potential devastation of potato early die. Flashing back to her family farm and the chicken manure that had proven so inhospitable to life, she directed research into the effectiveness of different manures and compost blends in attacking nematodes.

“Unsurprising to me, because I already suspected it, chicken manure was the most effective in reducing nematode numbers,” Quintanilla said. She was a bit taken aback, however, at how little was needed to produce an effect: “Even at 0.1% in the soil, it still had noticeable differences that we could measure with statistics.”

Quintanilla and her team, including Luisa Parrado, a doctoral student who helped author the project proposal, also tested a compost mix from a Michigan producer made up of chicken manure, dairy manure and wood ash. That testing found that wood ash and chicken manure were more effective than dairy manure.

“Some of the organic acids that were produced in the decomposition of the compost were very likely playing a role in this. Higher levels of some organic acids were associated with higher levels of control,” Quintanilla said. “I also think that there’s some involvement of anaerobic conditions in the soil — in other words, not enough oxygen for the nematodes. They’re drowning because of the bacteria that are decomposing.”

Those observations produced some key questions.

“How do we make this compost more effective?” Quintanilla said. “Maybe we can modify the recipe of some of these composts or manures to particularly target this problem. Also, are there certain microbes in the compost or manures that are having more effect than others?”

The NIFA funds, which became available June 1, will help answer those questions.

Proof in the soil

Mark Otto, owner of Agri-Business Consultants in Lansing, Michigan, has helped clients overcome challenges inherent in growing potatoes for decades. He’s worked with four generations of nematologists at Michigan State, including Quintanilla.

Soil health is a key defense for crops and a focus of Otto’s efforts.

“I’ve got clients that use applications of a compost blend on 100% of their acreage,” he said. “Growing potatoes with the amount of tillage that we do is hard on soil, so it’s something we have to work hard at managing.”

Otto said most of the growers he works with use low rates of compost, as they don’t have animals on their farms and can’t afford tons of manure and compost.

“What we’re doing has a priming effect, but under the right conditions, we can see big responses, where you get through a problem because you’ve got better nutrient retention capability,” he said. “If we get a big rain after about the first of August and leach out nitrogen, we can’t add back nitrogen, so we can lose a lot of yield. When you get those kinds of environmental conditions, that’s where these compost blends pay off more than normal. I’m convinced that we see anywhere from a 10% to 15% yield bump with what we’re doing.”

Casey Carr, agronomist at Sackett Potatoes in Mecosta, Michigan, has also noticed benefits, including reduced nematode pressure, since the farm discontinued fumigation in 2015 in favor of reduced tillage, compost usage and cover crop rotation.

“We have a more vigorous crop, a more vigorous root system, and the plants stay healthy longer for more of the growing season than in the past,” she said. “Plant pathogens and plant parasites thrive in unhealthy soil, and we think what is happening is that we’ve improved our soil health over time.”

The change was made because the cost of fumigation had begun to outweigh the benefits, Carr said. The farm last fumigated in 2014.

“The benefits of crop rotation and cover cropping and compost are not immediate,” she said. “It was a challenge to work through those first few years. We had to be really patient.”

Sackett samples for nematodes in the fall, in the spring and twice in the summer, Carr said. Fields with less soil resilience have not seen a noticeable drop in nematodes, she said, and are a work in progress — and indicative of the constant vigilance needed to fight potato early die complex.

“Verticillium, which is one piece of the potato early die complex, comes in on feed, and you establish it in your soil after growing crop after crop of potatoes,” she said. “There’s potato early die risk involved if you plant potatoes. The risk is always there.”

Quintanilla hopes that her lab’s research can arm growers to better manage that risk.

“We are trying to understand the dosages that are needed, the exact compost that we need to use, the compost and manures that are the most beneficial, the microorganisms that are most affected, (and) how can we increase these numbers of the most beneficial microorganisms,” she said. “Our objective is to increase sustainability so that you can reduce some pests and diseases, reduce some chemical control, reduce some of the cost to the grower and increase the sustainability so that a field can be productive and suppress some of these pests and diseases for longer.”