Pacific Northwest wildfire, smoke risk presents potential harm to potato plants

Where there’s smoke, there’s usually fire, and that’s certainly been the case in the Western U.S. in recent years.

The increasing number of Western wildfires — which cause smoke and higher levels of ozone pollution — along with Pacific Northwest (PNW) heat waves and reports of a megadrought have farmers facing an ongoing agricultural crisis of global dimensions.

At the 2022 Idaho Potato Conference, Mike Thornton and Carrie Wohleb addressed present and future concerns and measures to be taken by potato growers facing these ever-increasing natural disasters during the growing season.

Wohleb, an associate professor and potato, vegetable and seed Extension specialist at Washington State University, addressed the potential impact of wildfire smoke, residue and ozone pollution on potato crop development in the PNW.

“Wildfires are a problem because they release a large amount of carbon dioxide, brown carbon and black carbon particles and ozone precursors, like hydrocarbons that when they mix with the air form ozone,” Wohleb said.

Ozone is one of the more damaging or harmful pollutants for plants, she added. “It enters the stomata or the pores on the leaves surfaces during normal gas exchange processes of the plant or taking in CO2 and then once inside it forms reactive oxygen species that can damage cell contents and cell membranes.”

Long-term exposure to high concentrations of ozone may result in leaf and plant cell damage. While chronic exposure to moderate or lower levels doesn’t seem to cause visible injury to leaves, it may still cause some impairment of plant function and limit plant growth.

Potato plants, for example, tend to show a stippling symptom — small black spots — all over the leaves from ozone exposure.

“New leaves that are produced after the ozone and other pollutants have dissipated can be perfectly normal,” Wohleb said. “This is especially true for indeterminate potato varieties like Russet Burbank, that tend to continue to put on new growth throughout the growing season.”

Whereas plants that have more of a determinate growth pattern and don’t develop more leaves after flowering, such as Russet Norkotah, tend to show more smoke damage.

“In addition to wildfires, ozone can be formed by lightning strikes,” Wohleb said. “So, you might see some of those stippling symptoms after a storm.”

She cautioned to be mindful of environmental changes created by smoke combined with weather conditions when managing your crop.

“During smoky haze, for instance, you might find that the crop needs less water and you should irrigate less,” she said.

Smoky conditions sometimes play positive roles in plant development, Wolheb said.

“The CO2 from smoke is not really a negative factor, and it might even be a positive factor as long as low light from smoke is not limiting photosynthesis first — that’s that law of limiting factors,” she said. “Temperatures are often moderated when there’s smoke. So, for many crops the smoke cover may actually be a positive factor if it helps to cool things down when it would otherwise be really hot out.”

The proximity to wildfires makes a big difference in the impact on the crop.

“The closer you are to those fires, usually the bigger difference it makes,” she said.

Heat stress

Mike Thornton, professor of plant sciences with the University of Idaho, followed Wohleb with a presentation on the continuing impact of heat stress on potato crops during the past decade, with special emphasis on the impact to the 2021 potato crop.

“Here’s the main message,” Thornton said, “it would be great if we could just say, ‘hey, yeah, heat’s bad for potato growth and therefore yields are down,’ but it’s way more complicated than that.”

The problem is not limited to heat stress, it’s about water uptake, irrigation management and how to supply plants with necessary nutrients.

Potatoes are a cool-season crop that best thrive when temperatures are in the mid-70s during the day and mid-50s at night, similar to conditions in the Andes Mountains, where the crop originated. Potatoes adapt somewhat to warmer temperatures, but it’s continuous high temperatures that damage the plants.

“If we have a day or two of hot temperatures, (there’s) very little impact” Thornton said. “If we have five to 10 days where it’s 95, 100 degrees, that really starts to hurt the crop.”

High heat complicates every other decision potato growers make.

“I like to think of it as your margin for error. When it’s hot you don’t have near the margin of error in your irrigation management, you don’t have near the margin of error in your nutrient management, in your pest management, everything else becomes more critical because if you add one of those stresses to heat stress than you really get in trouble real quick,” Thornton said.

The focus on the impact of heat stress on potato plants has become even more important with heat indices projected to continue rising throughout the 21st century.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the average temperature in the Pacific Northwest has increased by 1.5°F since 1920. It is projected to increase by 2°F in the 2020s, 3.2°F by the 2040s and 5.3°F by the 2080s. The USFWS model also projects wetter autumns and drier summers during the same time period.

Thornton said the 2021 growing season wasn’t just “unusually hot,” it was “unusually hot early.”

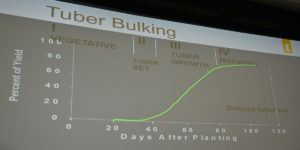

Heat stress during tuber initiation is particularly impactful on potato plants. If stress occurs prior to tuber initiation the plant will often not develop tubers but instead will continue growing a greater canopy of leaves.

In 2020, the first 90-degree days occurred in mid-July. Last year, the first 90-degree day was June 3.

“The timing of the stress in terms of whether or not you have tubers when the stress sets or you don’t have tubers is really critical and that’s one of the things we saw this year (2021),” Thornton said.

Heat impacts potato plants in three ways:

- Delaying or affecting the duration of production.

- Affecting the plant’s efficiency of production.

- Affecting the tubers’ external quality.

If tuber initiation is delayed 20 to 30 days due to early season heat stress, tubers may not have enough time left in the season to bulk up.

“We start getting into September, days start getting shorter and we don’t have the light available for photosynthesis,” Thornton said. “Temperatures go down and get too cold and (then) we have things like plant senescence.”

Heat stress after tuber initiation can impact the efficiency of tuber development in the face of continued high temperatures. Prolonged heat stress leads to vine growth over tuber growth, Thornton said.

Another important component in tuber development is soil temperature. If the plant’s row canopy has yet to close, tubers may develop internal defects when soil temperatures get above 70°F.

“So, it comes back to management,” Thornton said. “Anything that delays emergence, anything that gives you a spotty stand, anything that delays early development of the crop — if you have herbicide damage, if you have a nutrient deficiency, if you have rhizoc early in the season — that’s going to affect the plant’s ability to produce enough cover to shade that soil and reduce soil temperatures.

“If you have (that) and heat, that’s a really bad combination.”

The impact of heat on tuber development is greatly diminished if your plants can reach mid-bulking prior to heat stress.

“If we can get into mid-bulking when the tubers are about the size of a hen’s egg, heat after that is much less damaging,” Thornton said. “It’s that early development from just when the stolons swell to when the tubers get up to about quarter size is really the critical time.”

Water demands

Thornton also addressed the additional water demands plants require to cool down the ground inside the canopy in the face of heat stress.

“As the temperature goes up the crop’s water needs goes directly up with it and so when we have these hot days we have really high water demand,” Thornton said. “As the crop evaporates water it uses it to cool itself down, it’s using it to try to get below these temperatures that are stressful so if you go out even on a 100 degree day on a well watered crop and stick your hand down in the bottom of the canopy it’s significantly cooler.”

Thornton said in a year like 2021, growers can’t afford to fall behind on irrigation management.

“If you started the early-June section with really good moisture in the bank of the top two feet of soil, you were able to manage and draw down your moisture and not get to the stress threshold,” he said. “But if you started a little marginal on soil moisture and then you just kept getting behind because your system didn’t have the capacity to supply ¼” or ¾” of water everyday, all of a sudden you were stressing that crop continuously for water on top of the heat.”

Thornton pondered about the prospect of 2021 being a precursor to future conditions.

“I think one of the key questions for our industry here in Idaho is, ‘Is this a one-off or is this a glimpse into the future?’

“If the predictions for the next 29 years after 2040 are correct, they are saying a significant portion of eastern Idaho is going to have days over 100°F every year; same with central and western Idaho.”

He then re-emphasized that it’s not the single days over 100°F to be concerned about, it’s continuous days over 100° that stress the potato plants. He reiterated the need to begin planning now for a comprehensive irrigation management program for the future.

“I just want you to start thinking about: ‘Do I need to start thinking about my irrigation system? Do I have the capacity to meet what the conditions are going to be like in the future?’” Thornton concluded.