Organic potatoes continue to gain market share, although still behind other produce

Organic produce accounted for 15% of all produce sales in the U.S. in 2018. While the market share for organic potatoes is much lower than that, statistics show demand is on the rise.

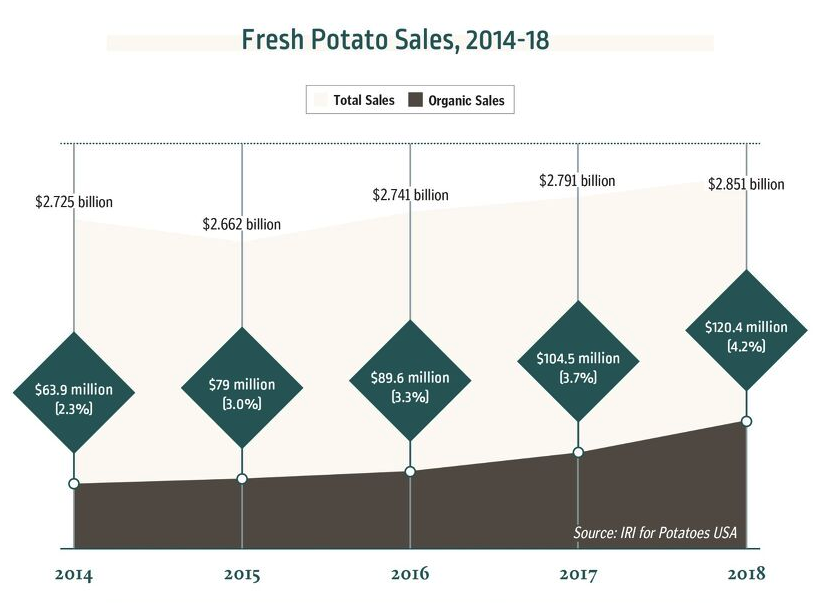

According to data from IRI compiled for Potatoes USA, organic potatoes accounted for 4.2% of the $2.851 billion in fresh potato sales in 2018. The $120.4 million in fresh organic potato sales was nearly double the sales amount in 2014, when the market share was just 2.3%.

“I think there is a place in marketplace for both organic and traditionally produced potatoes. It’s more challenging for organic growers on a product that’s grown in the soil because of all the soil pathogens and viruses. It’s hard to control those without conventional tools,” said Potatoes USA CEO Blair Richardson. “Notwithstanding that, there is certain demand for that category. I think the marketers and sales companies and growers looking at that are doing a good job of it. From my perspective, whether it’s grown conventionally or organically or any other set of terms, that’s the choice of the grower.

“At the end of the day, they’re all potatoes.”

With the anti-carb diet movement of recent decades, potatoes have received negative attention, often labeled as empty carbs. The New York Times even called fries “starch bombs” in a 2019 article.

Richardson noted the public perception of the vegetable, which is high in potassium and vitamins C and B6, has come a long way in recent years. Potatoes USA even started a marketing campaign in 2018 geared toward the high-endurance athletic community, such as marathoners and cyclists, called “What Are You Eating?”

“We’re using different vehicles, different tools to get that message out there,” Richardson said. “This is allowing consumers to take a new look at potatoes and as we continue down that path, we’re going to have even greater demand for potatoes.”

The reason that the market for organic potatoes has lagged behind other produce could be multifaceted. Perhaps the overall market for the vegetable and challenge of growing it, as Richardson noted, has discouraged organic growers from making it a priority. Or, perhaps the presence of a kill step because potatoes are cooked, has made buying organic spuds less of a priority for the general public. Bagged salads, strawberries and apples — the most prominently consumed organic produce, according to the Organic Trade Association — are eaten raw most often.

Getting in at the ground level

Nature’s Circle Farm in Aroostook County, Maine, was founded in 1996 by Dick York. He owned 100 acres that had been in the family for decades, although had not been farmed in years. York discovered Eliot Coleman’s books on organic growing and was intrigued. Dick’s daughter Meg York got involved with the farm in 2004. She is now co-owner and oversees sales and marketing. (Dick, now 72, is still very involved.)

“In 1996, in northern Maine, there was very little knowledge of organic vegetables and not much of a market for them,” Meg York said. “A few years later, my dad got involved with Whole Foods and Hannaford’s (supermarket chain). … They wanted him to grow organic potatoes, so he started with organic potatoes, but he had to increase storage and increase land.

“That kind of changed the whole plan of the farm. It went from a hobby to an actual business.”

Nature’s Circle now grows 300 acres of potatoes and other crops, including beets, squash and cabbage, among a few others, all certified organic. Meg credits her father for growing the business, which he did through a lot of internet searching for customers. Dick’s primary profession was in sales, and he saw organic food as a burgeoning market.

“It was really important for him to be sustainable,” Meg said. “My dad is a salesman, and he saw the organic labeling as a good marketing strategy. … I haven’t had to do much work in finding markets – they’re there.”

Markets that sell organic and conventional produce are beginning to display products differently, Meg noted, saying that it’s much more common to see organic and conventional potatoes side-by-side instead of in different areas of the department. “The prices are actually more comparable than they ever have been,” she said. “Organic is higher, obviously, but it’s not dramatic.”

Nature’s Circle has maintained some key customers over the years for their fresh potatoes; they sell very few potatoes to processors. The farm is about 80 acres of organic seed potatoes and that’s where the Yorks see their future.

“The seed business is where we’re really trying to grow,” said Meg, who the amount of fresh organic potato growers is increasing, both locally and nationally. “There is getting to be more competition.”

Nature’s Circle currently sells seed potatoes to New England growers, as well as to distribution centers in Ohio and Kentucky. Their seed customers numbered from “10 to 15” five years ago to about 40 today.

Communication

As CEO of the National Potato Council (NPC), Kam Quarles and the NPC staff work closely with policymakers and governmental agencies in Washington, D.C. Quarles said public demand can sometimes be conflicting, using the growth of organic food and plant-based meat segments, as two opposite ends of the spectrum.

“Everybody in agriculture is trying to figure out where all these things fit,” Quarles said. “Some of the signals coming from consumers are a little confusing in that you’ve got a huge group of folks who say they don’t want a huge amount of technology in agriculture, that they want to go back to this sort of idyllic way of producing our food. Then, you have this other group of enthusiast consumers for these meat alternatives that couldn’t exist with huge amounts of technology and are constructed in a lab.”

Quarles said people in agriculture, whether organic or conventional, should be communicating with each other. “I think production agriculture, we want to have a constructive conversation with everyone over ensuring you’re using the best science around, including crop protection tools that are often necessary to make sure your crop is healthy,” he said.

Ultimately, the public thirst for transparency from food producers is a good thing, he added.

“(It) creates a real opportunity for production agriculture,” Quarles said. “(Growers) have spent decades and tens of millions of dollars in aggregate to put all these systems in place to deliver food to the table. They have a great story to tell. It’s our burden that we tell an accurate story about how all this very complicated supply chain fits together.”

Top Photo: Rainbow Organic Potatoes are distributed by Alsum Farms & Produce in Wisconsin. (Alsum Farms & Produce)