New potato cultivars: A look at some emerging varieties

Whether it’s to perfect shape and size, improve storability or protect against disease, potato breeders have their hands full meeting processor and consumer demand.

Five experts offer insight into their needs, and talk about what’s coming down the potato pipeline in terms of new varieties — today, tomorrow and in the not-so-far-off future.

Different regions have different needs, which is why there are breeding programs across the country. David Douches, who leads the breeding program at Michigan State University, deals mostly with chipping varieties. His breeding program focuses on scab and PVY resistance for long-term storage.

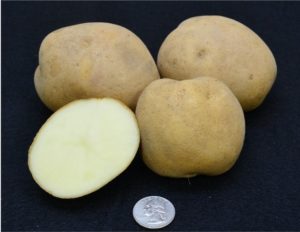

“I feel like we’ve been making good progress in scab resistance and the virus resistance,” said Douches, who pointed to the program’s most recent release, Mackinaw (top photo and right).

Mackinaw offers resistance to scab and PVY, and stores well all the way into early July. Processors will like that the variety is high in starch. The variety is currently being tested in field trials across the country.

Douches said they’re also trying to add the PVY-resistance trait to other varieties.

Out east in New York, Walter de Jong heads the breeding program at Cornell University, where he’s also focused on chipping varieties. The traits he’s primarily concerned with are shape and size. Industry stakeholders, he said, are looking for smaller, rounder varieties with relatively high starch content that give good fry color out of storage. Smaller sized potatoes are a better fit for processors who wish to sell in smaller bags.

They also need some level of resistance to common scab. Common scab causes pits in tubers, creating waste during peeling. “It’s expensive to control,” said De Jong. “Unless you change soil pH, which causes all sorts of other problems.”

Breeding for resistance to common scab is not difficult. “I guess the real challenge in potatoes tends to be getting everything that growers want, which is impossible, so it’s a balancing act,” said De Jong.

The team at Cornell developed New York 163, a new chipping variety that showed promise. Its fry color coming out of storage was lighter than they’d ever seen. But some unusual results surfaced during trials, though. The variety had a propensity to develop blisters or bubbles during frying. “The genetics of blistering are unknown, but some potatoes are prone to it,” he said.

De Jong is waiting to see if those results reoccur in future trials. Blistering is a trait they will be paying attention to in the future.

De Jong is unique among American potato breeders in that he also focuses on resistance to the golden cyst nematode, a problem unique to New York growers. Golden cyst nematode is a quarantine pest that can survive in the soil for up to 30 years. It is very difficult to control, said De Jong.

“If we weren’t keeping on top of it in New York, the whole nation would care,” he said. “It’s only because we’re keeping it contained that they don’t have to care. But someone has to care.”

In a side project, De Jong is trying to breed a potato variety with orange flesh. Potatoes with interesting color patterns do not represent a large part of the market, but they do represent part of the market, said De Jong. At the moment, there are no commercial varieties with orange flesh.

In North America, the preference is for white potatoes, especially in the chipping and fry markets. Yellow-fleshed potatoes are making some gains in the fresh market, said Jan van Hoogen, general director at Dutch potato breeding company Agrico.

Agrico breeds almost exclusively yellow-fleshed varieties. Van Hoogen said 10 percent of yellow-fleshed table varieties in the U.S. are developed by European breeders.

“In North America, everything is based on Russet Burbank, and it’s very difficult to find anything that comes close to it,” said Van Hoogen.

“It’s a complicated market,” he said. “It’s a huge market, but it’s complicated.”

Robert Graveland, research director at HZPC, another major potato breeding company based in The Netherlands, agrees with Van Hoogen’s sentiment. North America is unique in its preference for white-fleshed processing potatoes and russet skin. European breeders, he said, focus on sustainability, so reducing the environmental footprint of the potato. Like most breeders, much of HZPC’s focus is on stability of yield and performance against stressors.

New PVMI varieties available

The Potato Variety Management Institute (PVMI) has two new promising potato varieties available to seed growers, and two promising varieties are coming down the pipeline. PVMI Executive Director Jeanne Debons is responsible for marketing the varieties to processors and seed growers. Seed growers, she said, typically won’t grow a variety unless processors have expressed interest. Processors have expressed interest in both Galena Russet and Rainier Russet.

The first, Galena Russet, is a high yielding, medium-to-late French fry processing potato with attractive tubers. It has cold sweetening resistance and high protein content. A high percentage of its overall yield meets U.S. No. 1 grade. While dormancy length of Galena Russet is approximately 20 days shorter than Russet Burbank, it is more resistant to the viruses PVY, PLRV and tuber net necrosis than Russet Burbank and Ranger Russet. But it is slightly more susceptible to foliar early blight.

A superior potato with regards to taste, Rainier Russet has high fresh pack-out and the average tuber size is 10 ounces. It also offers long dormancy. When compared to standard varieties, Rainier produced a significantly higher percentage of U.S. No. 1 yields. It has high protein, high antioxidant levels, high specific gravity, light fry color, low acrylamide levels, and few internal and external tuber defects.

For non-seed growers, these varieties are three to four years out. Both varieties should be available to seed growers as of next year.

For non-seed growers, Debons highlighted two varieties of interest: La Belle Russet and Pomerelle Russet.

In comparison to Russet Burbank, La Belle Russet is an early to medium-maturing variety with good early-season yields of oblong-long, medium-russeted tubers and excellent dormancy. It also has greater resistance to tuber malformations and most internal and external defects. It’s an excellent storage potato that can be stored up to nine months, said Debons.

Pomerelle Russet is an early-maturing, dual-purpose potato that produces moderately high early-season yields. Debons said it produces consistent, attractive tubers that are resistant to internal and external defects.

“It also has good storage, but probably not as good as La Belle,” she said.

It maintains acceptable fry color for about 180-200 days in storage at 48°F, which indicates some potential for processing out of short-term storage. However, its primary use appears to be as a high quality, early fresh variety.

Pomerelle Russet and La Belle were primarily fresh market potatoes, until McCain tested them. They’re suitable for both.

More information is available on PVMI’s website.

Top photo: Mackinaw white potatoes in storage. (Michigan State University)