Freezing the future: U of I cryopreservation project holds potential

A new method of cryopreservation of potato germplasm at the University of Idaho (U of I) holds the potential to enable researchers to freeze seed samples efficiently and contamination-free for decades — if not longer.

The university’s Seed Potato Germplasm Program is exploring a new cryopreservation unit using liquid nitrogen vapor, which freezes seed potato tissue for long-term storage at negative 320° F. Vapor-phase units are more efficient and less prone to sample contamination than cryopreservation units that freeze samples directly in liquid nitrogen, according to the university.

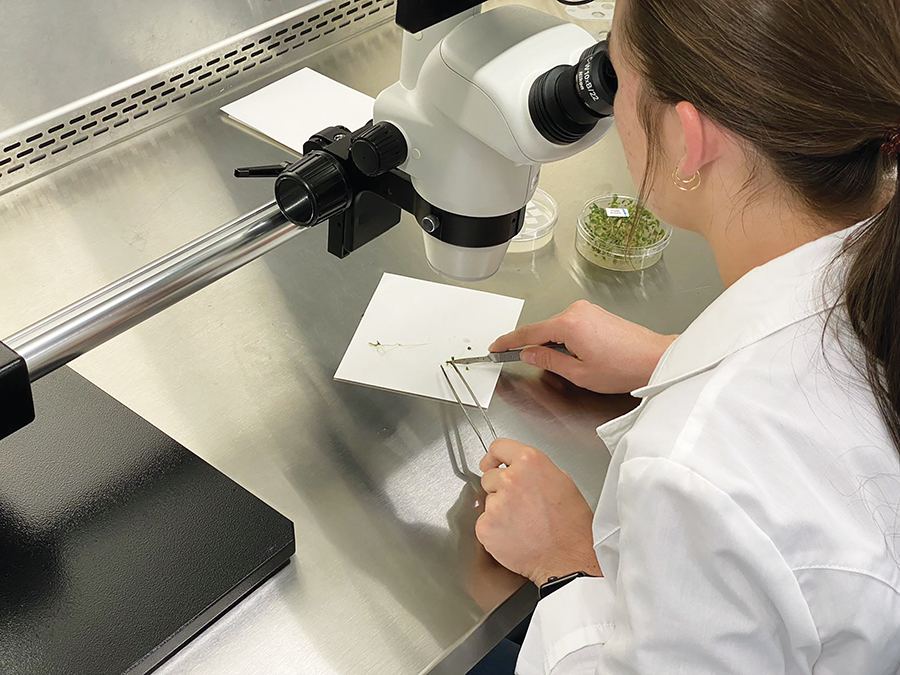

The new technique is being studied at the university’s state-of-the art Seed Potato Germplasm laboratory, which opened in March 2022. The laboratory produces disease-free potato germplasm for domestic and international seed potato growers and researchers.

Shannon Kuhl, interim lab director, learned about the vapor technique last fall on a trip to Peru’s International Potato Center, where she underwent cryopreservation training.

“I was very impressed by the center in Lima and what they have accomplished, especially with their cryo system,” Kuhl told Spudman. “They currently have approximately 5,000 potato accessions in cryo storage, and a staff of 15-20 people designated solely to cryo processing.”

U of I’s vapor-phase cryopreservation unit will have the capacity to store meristems for up to 1,800 varieties of potato and breeding clones, according to the university. Meristematic tissue, the actively growing part of a plant located at the tip of the shoot, can be used to reproduce an entire plant.

EXACTING SCIENCE

The droplet vitrification preservation process requires precise execution.

A droplet containing 10 meristems, each about a millimeter long, is vitrified on a foil strip and placed in a 2-milliliter vial.

“Once we’ve gotten the droplet of meristems on foil, it’s then treated with cryoprotectants, to increase viscosity,” Kuhl said. “We are removing the water in the plant cell so that when it is exposed to freezing temperatures, the cell wall doesn’t rupture and destroy the plant cell. The goal is a glass-like state called vitrification, not ice formation.”

Boxes, each containing 100 vials, are then stored on racks above liquid nitrogen inside a 495-pound tank 61 inches tall and 31 inches in diameter.

“It’s a pretty technical process,” Kuhl said. “You have to make sure that every step of the process is correct, otherwise your plants are not going to make it through.”

Kuhl said the lab currently has some samples in cryopreservation, and viability testing has begun.

“At this point, we have about a 5% viability,” she said. “About 5% of the plants that we’ve preserved, we’ve been able to revive. This is not good enough yet for long-term storage. For long-term storage, we need to have a minimum 30% viability.”

Before embarking on cryopreservation, Kuhl and her staff, including U of I students, preserved germplasm by growing plants and creating clones using stem cuttings every four to six weeks. That time- consuming method can also lead to genetic mutations.

Using the new technique, the lab aims to preserve 100 to 150 meristems

per cultivar while periodically thawing a sampling of meristems to test for viability.

Cryopreservation can also help eliminate viruses in new clones submitted to the lab for storage and distribution, at a faster pace. The current method of cleaning new clones involves a combination of chemotherapy and heat exposure, repeated over several cycles of cutting and regrowing plant stems for a year and a half.

Cleaning a clone in a cryopreservation unit, by contrast, takes just a few months, as meristematic tissue is frozen for about a week and then thawed and regrown into a viable plantlet.

“Once we’ve gotten those clean potato lines, we will maintain them in tissue culture,” Kuhl said. “All of our material that goes out is certified pathogen-free.”

Saying that with confidence, Kuhl said, is a rewarding aspect of her job.

“Any time we send out material, we know that it’s clean material and we’re doing good things for the industry by keeping those pathogens to a minimum,” she said.

WORLDWIDE REACH

The research advances are being aided by a $50,000 grant from the Atchley Foundation Charitable Trust, started by Ashton seed potato farmers Clen and Emma Atchley, who met while attending the university.

Emma Atchley is optimistic that the research will produce dividends for early generation seed farmers and potato variety development programs.

In the nascent days of their operation, unsatisfied with the quality of early generation seed received from more remote locations, the Atchleys turned to U of I to obtain germplasm.

Emma Atchley said beginning seed production with disease-free material from the university has reduced the prevalence of certain diseases and eliminated potato leafroll virus as a disease of concern.

“For 30-plus years, we’ve never had a disease problem,” Emma Atchley said in a news release from U of I. “We can’t say enough about having that facility at the University of Idaho.

“It’s a worldwide industry, we have worldwide recognition, and the state should have world-class research and world-class facilities to support that research.”

U of I annually ships more than 300,000 disease-free potato plantlets and roughly 2,500 pounds of mini- tubers to researchers and seed growers worldwide. Mini-tubers are produced by establishing lab-grown, clean in-vitro plantlets in a greenhouse, with the resulting tubers planted the following year by seed producers.

About 90% of the potatoes grown in Idaho and 60% of the spuds raised nationwide originate from U of I, which started its germplasm program in 1983, according to the university.

“Our main goal is to serve the potato industry and help growers have productive and positive experiences with their crops and harvest,” Kuhl said. “We do everything we can to help growers be successful.”

And just how long might seed samples be able to remain frozen?

“It’s unknown at this point,” Kuhl said. “Decades, for sure, and possibly even centuries.”