Advancing PEF technology to the potato chip industry

Advances in Pulse Electric Field (PEF) technology in the food processing arena represent both cost savings and increasing measures of sustainability in the fry and chip sectors.

PEF was first discovered by German engineers in the 1950s. It wasn’t until the 1990s that applications in cell permeability and food processing were first developed in Europe.

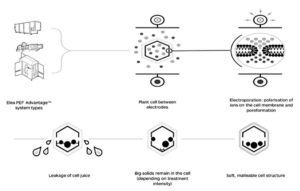

PEF technology exposes vegetable cell walls to short, micro-second bursts of electricity as it passes through a water bath. The pulse electrical field creates a permeability and tissue softening of the cell wall resulting in leakage of cell juice and a loss of reducing sugars and amino acids in the course of the process.

With refinement of PEF technology in the 1990s came the first industry use by french fry manufacturers in Europe. During the first decade of the 21st century the technology was adopted by multinational companies globally, and today PEF technology is considered to be the industry standard in french fry production throughout the world.

The adoption of this new technology by french fry producers over the past decade has resulted in notable advances in sustainable measures in less use of water, energy and frying oil resulting in complementary savings costs.

Seeking to advance Idaho’s footprint in the potato processing industry, the Idaho Department of Commerce awarded an Idaho Global Entrepreneurial Mission (IGEM) grant of $291,770 to Boise State University (BSU) in partnership with Food Physics, based in Boise, on Feb. 23, 2021 to help Food Physics introduce PEF technology to the potato chip and snack food industry.

IGEM grants serve as a bridge for university researchers to collaborate with Idaho private sector businesses and through these partnerships enhance, cultivate and potentially establish new economic opportunities in the state.

The grant was awarded to research and advance development of PEF technology on reducing sugars and amino acids in potatoes ultimately resulting in a potential reduction of acrylamide in the production of potato chips.

McDougal, a BSU professor and chairman of the Chemistry and Biochemistry Department, said the grant-funded research will focus on potato chip production, but also will include other root vegetables.

“We’ll be able to hire a Ph.D. scientist that will be able to work between Food Physics and Boise State,” he said. “It (the position) will be an integral liaison to bridge the scientific gap between the private industry and the academic environment.”

McDougal said that the grant will also provide job opportunities for students and help prepare them for future employment.

“The students that work on these types of projects, it is research that has direct relevant value for the industry, so they gain skills and training that is directly applicable in the industrial setting,” he said.

Food Physics is the exclusive licensee of PEF technology systems for North America, Ireland and the United Kingdom and works with DIL, a German based-company and its food technology partner Elea. The grant is an opportunity for the company to market a technology to the potato chip and snack industry that has become the industry standard by french fry producers.

“The luxury that this grant provides us is to kind of go deep for a company that frankly doesn’t have the financial fire power yet to go that deep,” said Jim Gratzek, the technical director at Food Physics in Boise. “Big companies have people who can do this and frankly they have labs, we don’t.”

Ongoing technological advances in food processing techniques have resulted in advances in sustainability measures along with a complementary reduction in acrylamide, a carcinogen that develops in foods cooked at high temperatures.

McDougal and his BSU students and staff will be providing Food Physics with data specific to the impact that PEF has on the potatoes.

“We do the reducing-sugar analysis using a combination of liquid chromatography with charged aerosol detection,” said McDougal. “We do free amino acid analysis by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry and then we do the acrylamide analysis by liquid chromatography and triple or quadruple mass spectrometry.”

Gratzek is cautious when discussing the impact PEF has on reducing the amount of acrylamide in fried foods. He presents PEF as a “technique when applied with other things” can result in lower acrylamide levels.

“Not that PEF drops acrylamide, but PEF changes say the leaching phenomenon into water, which it does, it also changes the frying rates, which it certainly does, both of which will lead to lower acrylamides,” he said.

“Sugar, temperature, time, moisture level — those are all the inputs for how much acrylamide you get at the end of a frying process,” he added.

The reduction of solids in the form of reducing sugars and amino acids allows potato processors to replace or reduce the amount of hot water blanching or pre-heating in french fry and chip production.

“If blanching is used to soften alone, it (PEF) can eliminate the blanching process,” said Gratzek.

Another cost-saving advantage is the reduction in the wear of the cutting blades used in the fry and chip making process. The PEF technology softens the cell walls making potatoes easier to cut.

“The cutting is much more smooth, so you’ll have a lot less what’s called specific surface area,” Gratzek said. “So, that can be coupled with the fact that the water comes out much more readily and with less energy leads to lower oil absorption into the french fry or the potato chip.” Gratzek added that is not a huge amount at this point, 5-10%, but he hopes to further study the frying process with McDougal.

PEF technology has become the industry standard among french fry manufacturers over the past 20 years and is now being adopted incrementally by some of the chip and snack food producers. According to Carl Krueger, head of engineering at Food Physics in Boise, Europe is leading the technological transition, much as it did in the french fry industry.

“The last couple of years has seen an expansion of PEF utilization in potato chips in Europe,” Krueger said. “That’s been significant. Kind of like where we were in french fries. We’re a little bit kind of riding those coattails behind them, but we have quite a number of potato chip manufacturers that we are talking with that are showing very strong interest in PEF.”

Krueger said that a common thread of concern among food manufacturers when considering new technology is what is known in the food industry as “mouth feel, a term used to describe that quality unique to a specific brand. Whether it’s a secret formula or the secret sauce, companies are extremely protective of their brand identity and preserving customer loyalty. No company wants to replicate the kind of public relations fiasco Coca-Cola faced in the mid-1980s with the introduction of “New Coke.”

“We actually ran into that with a large food service customer who didn’t want their product to change because we were changing technology,” said Krueger.

Krueger said that they were able to prove in a sustainable fashion that the PEF process would produce the exact french fry that they had always produced.

Gratzek believes that advances in PEF technology will help mainstream its acceptance in the chip and snack industry in the future, but he also recognizes that the food industry is not always quick to accept innovations.

“Technology adoption in industry, especially the food industry, is typically pretty slow,” he said. “It has to solve a significant problem, bring significant value in terms of a new product or innovation, or it has to save a lot of money.”

Gratzek thinks that one reason why PEF technology might be adopted faster in the future is because they’ve developed the knowledge and application techniques that typically is kept in-house by the chip manufacturers.

“I think that this grant is especially helpful for us in that it will allow us to do the research in Boise and Boise State such that we can with great specificity solve the issues that the customers have,” Gratzek said.

“If they want less oil, we’ll help them with that, if they want to keep the oil but lower, better frying rates, we’ll be able to help them with that,” he added. “In short, chips are more complicated than french fries, I think, maybe the problems in chips are a little bit tougher to solve.”

Gratzek said that approximately 20 of the PEF processors have been sold in Europe for multiple reasons.

“I suspect they’re buying them for acrylamide reasons, operational efficiency reasons and product quality reasons,” he said.